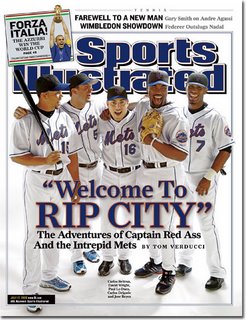

Through the doors to the New York Mets' clubhouse enter the young and the ancient, the slow and the swift, the homegrown and the mercenary, the charitable and the thrifty, the beautiful and (by official team balloting) the ugly, but never, for goodness' sake, the easily insulted.

"Welcome," catcher Paul Lo Duca says, "to Rip City, where we get on each other all the time."

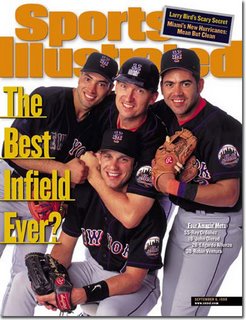

True to their home city's heritage, the Mets are a melting pot of cultures, customs, languages and, yes, occasional off-color salutations that somehow works. Backed by owner Fred Wilpon's money, shaped by a childhood dream of general manager Omar Minaya, who was born in the Dominican Republic and reared in Queens, and ably guided by second-year manager Willie Randolph, the Mets are the rare sports team that has found instant success after a nearly complete overhaul.

Of the 29 players on the active roster and disabled list at week's end, 16 joined the major league club since the end of last season. Only eight played for the Mets before Minaya was named G.M. 22 months ago. And yet, in a veritable New York minute, the Mets have become the best team (53-36 through Sunday) in the weakest league in years, with by far the biggest lead in baseball (12 games in the otherwise loser-filled NL East) and the thickest skins this side of a Friars' Club roast.

"Look at the personalities they brought in here," says closer Billy Wagner, an 11-year veteran who signed as a free agent last winter. "We're all extroverts. Me, Lo Duca, [Carlos] Delgado, Pedro [Martinez].... It's not like guys came here and were afraid to say something. I think that's why we clicked right away. This is the best clubhouse I've ever been involved in. And the secret is that guys can say anything they want to anyone at any time."

That's not to say that communication is always clear. There was the time, for instance, when backup catcher Ramon Castro ("the class clown," as Lo Duca calls him) visited Wagner on the mound in a crucial situation against the Blue Jays.

"How about a coo-ba here?" is what Wagner, born in the rural mountains of Virginia, heard his Puerto Rican catcher say.

"A what?" Wagner asked.

"Coo-ba," Castro said.

"Curveball?" Wagner finally deciphered. "I don't have a curveball!"

"Well, O.K.," Castro said. "We're not throwing that anyway."

Castro is even better known for his portrayal of ample-bottomed lefthander Darren Oliver, a vaudevillian impersonation that he performs on charter flights -- with the help of two airline pillows stuffed into the seat of his pants.

Not even Martinez, the three-time Cy Young winner, is immune from catching grief. After Martinez overslept for a game in Toronto this year, he was greeted in the clubhouse by Wagner, who took one look at Martinez's garish-colored outfit and bellowed, "I sure hope you're not late because you were out shopping for that."

Another time Martinez returned to his locker after batting practice to find his wildly styled loafers strung up from his locker, a team custom to mock fashion statements that invite ridicule.

"A lot of times you'll see somebody's shirt hanging in the middle of the clubhouse," Martinez says. "Cliff [Floyd], his stuff seems to be hanging a lot."

Floyd also has drawn attention for the music that accompanies each of his at bats at home: the theme to Sanford and Son. The tune was picked by Lo Duca, who thought it apropos for the oft-hobbled leftfielder.

And then there's Wagner, who still hasn't lived down the time he asked the clubhouse caterer if he could have a gallon of milk to take home to Greenwich, Conn.

"You're making $10 million a year, and you won't spring for a gallon of milk on the way home?" Lo Duca told Wagner. "Reach into that wallet once in a while, will ya?"

When the Mets are rolling, as they have been for most of the season, they seem to have it all: pitching (they were second in the league in ERA at week's end), hitting (first in runs), speed (first in steals), power (second in homers) and that immeasurable but unmistakable element called chemistry, which develops when you can, with only the finest intentions, refer to your teammates as Visine, Moses and Captain Red Ass.

So charmed are the Mets that they entered the All-Star break 20-8 (.714) in one-run games -- only six teams in the post-1961 expansion era have played better than .700 ball in one-run games over a full season -- and had flourished despite having to use 11 starting pitchers in their first 88 games.

"Their versatility is very impressive," Pirates manager Jim Tracy said last week as the Mets took three of four games from Pittsburgh. "They have switch-hitters who hit equally well from both sides; they have guys on the bench who complement one another, which makes it hard to match up with them late in the game; and they can run and pitch. They can win games in a lot of different ways."

If the Mets keep this up, they will break or challenge franchise records for runs, home runs, stolen bases and opponent strikeouts while accelerating Minaya's time line for a pennant. Minaya has said that his goal for 2005 was to restore the franchise's image -- Delgado, a free agent that off-season, chose to sign with the Marlins in January '05 rather than the Mets because he deemed Florida the better team -- and for 2006 was to contend for a playoff spot. With such a large lead in the division, however, Minaya's revamped agenda is to fortify his rotation to carry the Mets through three rounds of playoff series. Unless the team's '05 first-round draft pick, righthander Mike Pelfrey, who allowed three runs in five innings to win his big league debut last Saturday, sticks, Martinez, 34 and with a sore hip (he was placed on the 15-day disabled list last Thursday, retroactive to June 29), would be their youngest postseason starter, fronting Tom Glavine, 40, Orlando Hernandez, 36, and Steve Trachsel, 35. In a humorous but telling moment last week Glavine stopped short when he stepped into the trainer's room to find a deli-counter-length queue. "Oh, my goodness," Glavine said, "what number are we serving in the whirlpool, number 9?"

"When we went 9-1 on the road trip [to Los Angeles, Arizona and Philadelphia in June], that's when I knew we had a good team," Minaya says. "But we still can be better. It's all about pitching, pitching, pitching. That's what I'm looking for every day."

Says a rival National League G.M., "They were the best team we've seen this year. But like everybody else, there are questions about their pitching. Everyone's scrambling for starting pitching, and it's everyone's dilemma that there may not be anything out there better than what you already have."

With the Marlins keeping Dontrelle Willis off the market, Minaya's best option for obtaining a pitcher who would start one of the first three games of a postseason series would seem to be Barry Zito, a potential free agent at season's end whom Oakland would consider trading only in a deal that keeps the A's competitive this year. That could mean that Minaya would have to give up 21-year-old Lastings Milledge, an athletic, aggressive outfielder who's precisely the kind of player who fits Minaya's vision of how the Mets should play the game.

"I grew up a fan of National League baseball and teams like the Dodgers, Pirates and Giants," Minaya says, recalling some of the early adapters of integration. "I believe in a balance of speed, power and pitching, like the way those teams played ball. I always wanted a team like that. The Mets never were one of those organizations. Traditionally they relied on pitching in a big ballpark. I always wanted more athleticism, and from Day One that's what I've tried to do here."

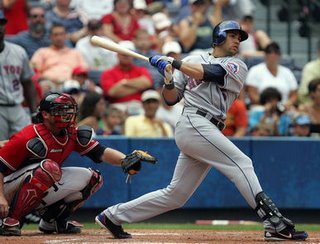

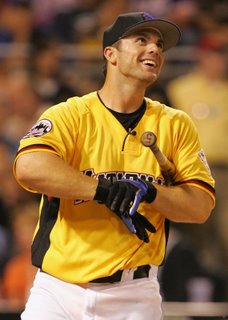

Minaya inherited two cornerstone players to help implement his blueprint: shortstop Jose Reyes and third baseman David Wright, both 23, who this week were scheduled to become the third-youngest pair of teammates to start an All-Star Game (trailing only Bobby Doerr and Ted Williams of the 1941 Red Sox and Dean Chance and Jim Fregosi of the 1964 Angels). Mr. Wright, as his many admirers refer to him, is fourth in the league in RBIs, with 74, though his matinee looks and knack for clutch hitting earn him no slack in the clubhouse.

"He's Visine," Wagner says. "You know, eyewash. One time he dove to catch a bunt he could have caught standing up. We all went like this...." Wagner rubs a finger along his eye, as if wiping away a tear.

"Wagner said that?" Wright says. "He talks a lot for a guy from the woods. You can't get in a word with that guy."

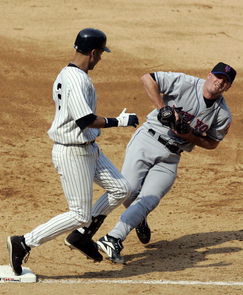

Reyes, meanwhile, is teaching Wright Spanish and, with his slashing hitting style and derring-do as a base runner, is schooling the rest of the league in how to disrupt opponents. "The best feeling of all," says Reyes, smiling, "is sliding headfirst into third base with a triple." (He leads the majors with 12.) So dangerous with his legs is Reyes that he is on pace to join MVP runner-up Lenny Dykstra of the 1993 Phillies as the only players since 1937 to score more than 140 runs without hitting 20 home runs.

"His improvement since last year is mind-boggling," Tracy says of Reyes, whose on-base percentage has risen from .300 in 2005 to .357 in '06. "The Mets are a good team, but when he's on base they're a different team. He takes them to another level."

Reyes has benefited from the counsel of 47-year-old backup first baseman Julio Franco, who was the first player Minaya tried to sign after being named Mets G.M. Minaya could not lure Franco away from Atlanta then, but he succeeded last winter by giving him a two-year contract.

"As long as I'm running a team, there are two guys who will always have a job with me: Rickey Henderson [a Mets special instructor] and Julio Franco," Minaya says. "That's how much I think of [Franco] as a person. He's like an extra coach on the staff. I knew he was as important to our chemistry as anybody."

Says Wright of the man who has spent some of his 29 pro seasons in Japan, South Korea and Mexico and has 2,546 major league hits, "He's talked to Jose and me about things like, 'If I only knew back then when I was young some of what I know now, I'd be looking at 3,000 hits.'" Adds Lo Duca, "That's Moses. He's all-knowing. Wisdom and knowledge, that's what he brings. He hasn't lost an argument yet."

For his part, Lo Duca seems ever in search of an argument, whether getting in the grill of his pitchers when they lose focus, spiking the baseball in a fit of anger at the feet of umpire Angel Hernandez or barking at Yankees third baseman Alex Rodriguez for styling too much after hitting a home run. "That's just me," says Lo Duca, whom Wagner refers to as Captain Red Ass. "Must be the Italian blood."

Minaya wound up with Lo Duca and Delgado, his cleanup hitter and first baseman, only after Florida's decision last winter to slash its payroll. Minaya knew a year ago that he needed a middle-of-the-order hitter, but he was unsure where to turn after a three-team midseason deal to get Manny Ramirez from Boston fell through when Tampa Bay backed out. (Minaya was prepared to trade Milledge in that deal.) "Power hitters like that just don't come on the market," Minaya says of Ramirez.

Then, on the final day of the general managers' meetings last November in Palm Springs, Marlins G.M. Larry Beinfest told Minaya, "We're prepared to talk about everybody except Miguel Cabrera and Dontrelle Willis." Says Minaya, "That started the ball rolling for the 2006 team." Delgado was the perfect fit: a premier power hitter, a close friend of quiet Mets centerfielder Carlos Beltran, who struggled in 2005 trying to be the Mets' franchise player, and a charitable soul whom Minaya calls "a better person than he is a player." The Mets gave up three young players to get Delgado on Nov. 24, then two weeks later sent another pair of prospects to the Marlins to get Lo Duca.

"I had three-year offers out to [free-agent catchers] Ramon Hernandez and Bengie Molina," Minaya says. "Then Lo Duca popped up. I always feel like when you have a bird in hand, you take the bird."

In between those trades Minaya signed Wagner to a four-year, $43 million contract, fulfilling a promise he had made to Martinez and Glavine. "I told them, 'At this stage in your careers, I promise you I will do everything I can to make sure you get the wins that are coming to you,'" Minaya says. "We went after B.J. Ryan and Wagner. I give the Blue Jays credit. They went out aggressive on Ryan, giving him five years right away. We needed Wagner after that."

Wagner did not become fully vested as a Met until May 21, when he saved a game against the Yankees the day after blowing a four-run lead against the crosstown rivals. Minaya, understanding that Wagner had to pass such a trial by fire, told him in the clubhouse after that save, "Congratulations. You just won us the pennant."

Minaya's blueprint has worked as well on the field as it promised to on paper. Martinez and Glavine have 18 total wins, half of which have been saved by Wagner. Beltran, buoyed by the presence of Delgado, is one of a franchise-record six All-Stars, sports a career-high .995 OPS and was recently named one of People magazine's 100 most beautiful people -- a designation that inspired a teamwide vote to determine the ugliest Met. (Castro, Franco and Eli Marrero tied for the honor. "Finishing in a very strong second place was David Wright," says Lo Duca.) Wright and Reyes, insulated by veteran stars, have blossomed without the added burden of being team leaders. Franco leads the league in pinch hits and stories told.

"Cleveland, that was the worst for team chemistry," Franco says. "We'd get 80,000 [fans] on Opening Day and 2,000 after that. By the All-Star break we'd be 20 games out, and guys were worried only about their stats, not winning. Now in Mexico.... "

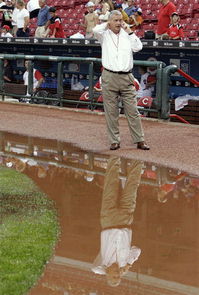

Still, Minaya is not satisfied. Sitting over a cup of Navy-bean soup last week at a New Jersey diner, the towers of the George Washington Bridge looming through the window behind him, Minaya, expert though he may be on the lay of this land, wore a countenance drawn more from concern than confidence. He wants his team to improve on grinding out at bats, the way he watched the Red Sox do while sweeping a three-game series from his club late last month. (The Mets went on a 3-6 slide against AL East powers Toronto, Boston and New York.) He knows he may need another pitcher. The architecture of these new Mets, he knows, is a work in progress. The concrete is still wet.

"What is New York Mets-style baseball?" asks Minaya. "That's what we're working on: to have something in place that lasts going forward. So that when you think of the New York Mets, you think of players who can take the extra base or take you deep. Power. Speed. Athleticism. We're getting there."